Author’s note: The data used to create the analyses (including charts and maps) included in today’s newsletter come from the National Center for Atmospheric Research or NCAR, a federally funded nonprofit research center headquartered in Boulder, Colorado. The Trump administration submitted a budget request at the end of May which slashes NCAR’s funding by 40%, jeopardizing these critical data streams regularly used by scientists and forecasters.

The Atlantic basin has been undergoing a metamorphosis of sorts over the past few weeks, shedding its hostile early season shell for an increasingly conducive look with the hurricane season’s traditional busiest stretch only weeks away.

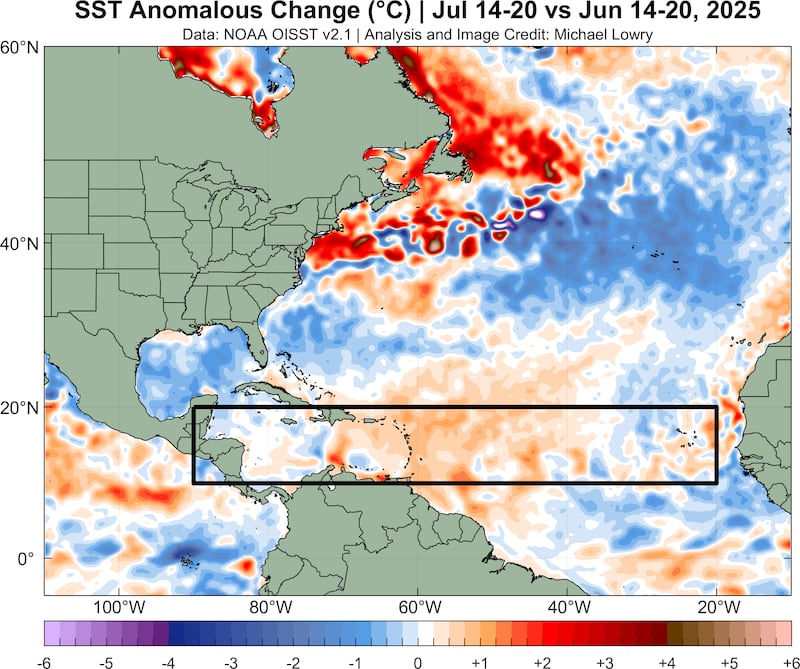

The most noticeable change has been the anomalous warming of the Atlantic Main Development Region or MDR, an important bellwether region between Africa and the Caribbean where most of our strongest hurricanes each season get their start. We discussed this warming trend in last Thursday’s newsletter, and it’s continued since, with anomalous warming – that is, after removing the seasonal warming you would normally expect from June to July – concentrated across the MDR belt and cooling in the subtropics east of Florida and across the Gulf.

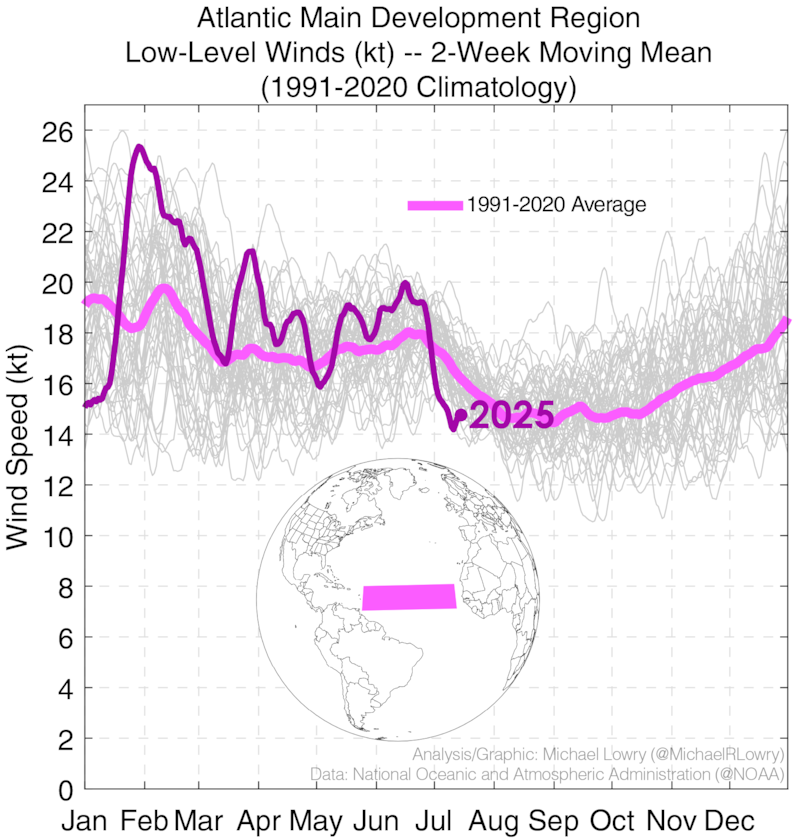

The warming is due to a weakening of the Bermuda High across the Atlantic, which has effectively turned off the strong east-to-west flowing trade winds from Africa to the Caribbean. After some of the strongest trade winds on record to start the year, and the strongest June trade winds since 1990, we’ve seen the weakest trade winds to start July on record (since at least 1979), and by a wide margin.

Will the abrupt MDR warming trend continue? Forecast models suggest so, as trade winds remain weak well into August, with additional cooling in the latitude belt north of the MDR (the so-called subtropics) that should further promote rising air and storminess in the preferred areas of the Atlantic.

Here we go with the MJO

Another factor working against development so far this season has been the general configuration of rising air and sinking air across the tropics.

In general, rising air over north Africa or the north Indian Ocean and sinking air across the eastern Pacific is the type of configuration that promotes storm formation in the Atlantic.

So far this year, that’s not been the case, with a stubborn configuration of sinking air over Africa plaguing the Atlantic with very hostile conditions.

The Madden-Julian Oscillation or MJO – an upper-level disturbance that circumnavigates the globe from west-to-east every 30 to 60 days, altering the upper-level wind configuration across the tropics – has had a tough time scouring away at the unconducive pattern over the Atlantic.

That’s forecast to change in the coming weeks as the rising side of the MJO is forecast to make an appearance in the Atlantic basin.

It’s to be seen if the MJO signal can overcome the persisting sinking air pattern over the Atlantic, but the signal is stronger than we’ve seen so far this season and will coincide with a seasonally favorable period beginning in August.

Moreover, we’ve seen a big shift northward of the monsoon wind regime into the Sahel region of North Africa, another signal that tropical waves rolling off Africa may be on the uptick in the weeks ahead.

Tropical waves rolling through the Atlantic

As we discussed in yesterday’s newsletter, a tropical wave moving into the Caribbean today and tomorrow (briefly designated Invest 94L) is unlikely to develop. The NHC dropped any chances of development overnight.

Meanwhile, another tropical wave emerging off Africa this morning will be moving through the tropical Atlantic this week. Both the American GFS and European model indicate a robust disturbance, but for now models remain muted on significant development.

CLICK HERE to download the Local 10 Weather Authority’s 2025 hurricane survival guide.

Copyright 2025 by WPLG Local10.com - All rights reserved.