Big outbreaks of Saharan dust – tens of millions of tons of mineral dust hoisted from the sands of North Africa into the Atlantic each hurricane season – typically peak around this time each year.

The band of sand that’s most concentrated between around 5,000 and 20,000 feet up is an important part of the climate, replenishing the soils of the Amazon rainforest each year and helping to stave off would-be hurricanes, especially during the summer months.

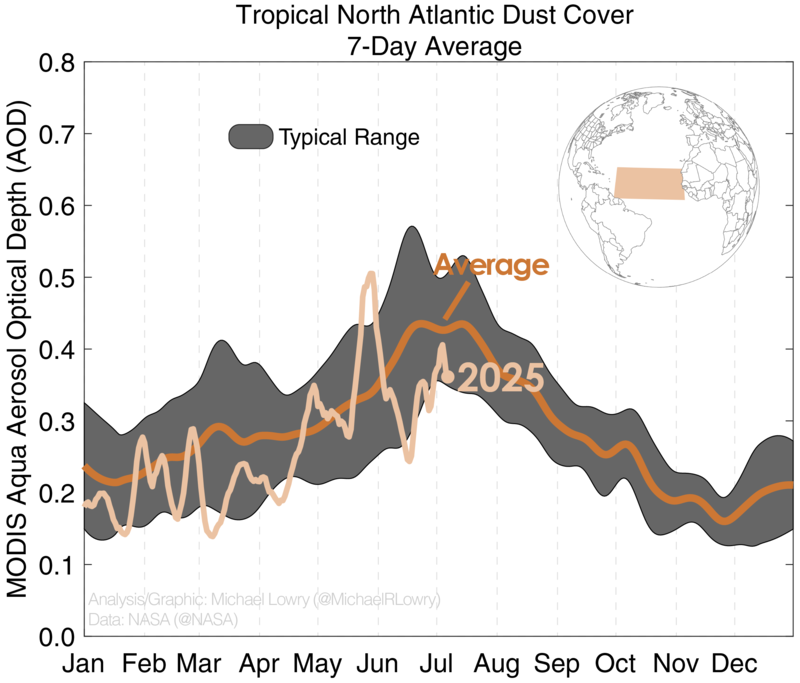

But despite spates of Saharan dust, including a large plume spreading deep into the Atlantic this week, dust coverage so far this hurricane season has been historically low. Since continuous satellite records of dust cover began in 2002, the levels of dust so far this hurricane season have been the second lowest on record, only behind 2023, something we discussed in this newsletter at the time.

Dust has been lowest west of North Africa, especially around the Cabo Verde islands and westward through the Atlantic Main Development Region or MDR.

On the one hand, lower dust cover could mean less hurricane kryptonite at our disposal this season, but it could also signal weaker tropical waves than usual, since tropical waves are the main vehicles that transport Saharan dust through the Atlantic.

The data certainly supports this idea. The strong current of winds at around 10,000 feet over North Africa – known as the African Easterly Jet or AEJ – has been noticeably weaker than average so far this hurricane season. This implies more anemic disturbances rolling off Africa in June and early July.

Something that may be contributing to these weaker tropical waves and lower dust cover is the developing Atlantic Niña, cooler than average waters straddling the equator in the eastern Atlantic.

The presence of these cooler-than-average waters helps to reduce the strength of east-to-west flowing winds along the African Easterly Jet to the north and lessens the available spin in the atmosphere that beefs up disturbances rolling off Africa.

It’s to be seen if the Atlantic Niña-like cooling will stick around deeper into the season (they tend to peak around this time of year – the one in 2024 petered out quickly in August), but for now it’s been working in our favor. Atlantic Nina episodes have been shown to dampen the frequency of Atlantic hurricanes, though the impact is less noticeable when not combined with a the abnormally warm waters of an eastern Pacific El Niño (we’re currently in neutral territory in the eastern Pacific, with only slightly above average conditions).

No development expected into next week

As we’ve previewed in newsletters this week, the Atlantic should stay mostly quiet for the next week or two.

Toward the end of July, storminess may start to pick up across the basin, but for now we don’t see anything to hang our hat on.

CLICK HERE to download the Local 10 Weather Authority’s 2025 hurricane survival guide.

Copyright 2025 by WPLG Local10.com - All rights reserved.